PETOSKEY, Michigan — The cemetery of this northern resort community, with a view of the glimmering waters of Little Traverse Bay, has a small Jewish section. On a recent Wednesday afternoon, the funeral being held here was the talk of the town.

A gold box holding the ashes of Lawrence Rubin sat, on a plain white tray, next to an embossed gold medallion commemorating the great civic engineering achievement of Rubin’s life. About 18 people gathered as Rabbi Debbie Masserano addressed the elephant in the room: a headstone for Rubin that listed his date of death as May 11, 2010.

“I have been wondering a lot about the long, 15-year wait,” Masserano told the assembled group during her eulogy. “The miracle of this occurring is so rare and so profound.”

Jewish tradition encourages burial of the dead as soon as possible. In Rubin’s case, burial took 15 years, during which time his cremated remains sat in a funeral home in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, unclaimed.

Only through happenstance, and in the nick of time, were they discovered and transported — across the grandiose bridge that was the central focus of Rubin’s life — to the cemetery for a proper burial next to his first wife Olga, under the headstone that had for decades borne his name.

What made the situation even more unusual was that Rubin was far from an anonymous figure. To much of the state of Michigan, he was a mensch: a literal bridge-builder. He was instrumental in the construction of the Mackinac Bridge, which connected the state’s two peninsulas by land for the first time when it was built in the 1950s. It is the country’s third-longest suspension bridge — after New York’s Verrazano-Narrows and the Golden Gate.

Working closely with New York-based Jewish engineer David Steinman on the design, Rubin oversaw the five-mile feat of engineering many thought impossible, then continued to run the bridge authority for 36 years. He also served as secretary-treasurer for the Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge, which links the two towns of the same name in Michigan and Ontario, Canada.

When Rubin died in 2010, at age 97, a public memorial was held at a park in full view of the Mackinac Bridge. The governor at the time, Jennifer Granholm, issued a proclamation in his memory.

And yet, after all the public memorials had ended, Rubin’s plot remained unfilled. Meanwhile, he sat, unclaimed, in the Dodson Funeral Home in St. Ignace, a town with only two Jewish families, his included. None of his friends, well-wishers or fellow congregants at Temple B’Nai Israel in Petoskey knew of his fate.

“We knew he had a place. There’s a marker there with his name and date of birth on it,” Karl Crawford, superintendent of the Greenwood Cemetery, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “But he was not there.”

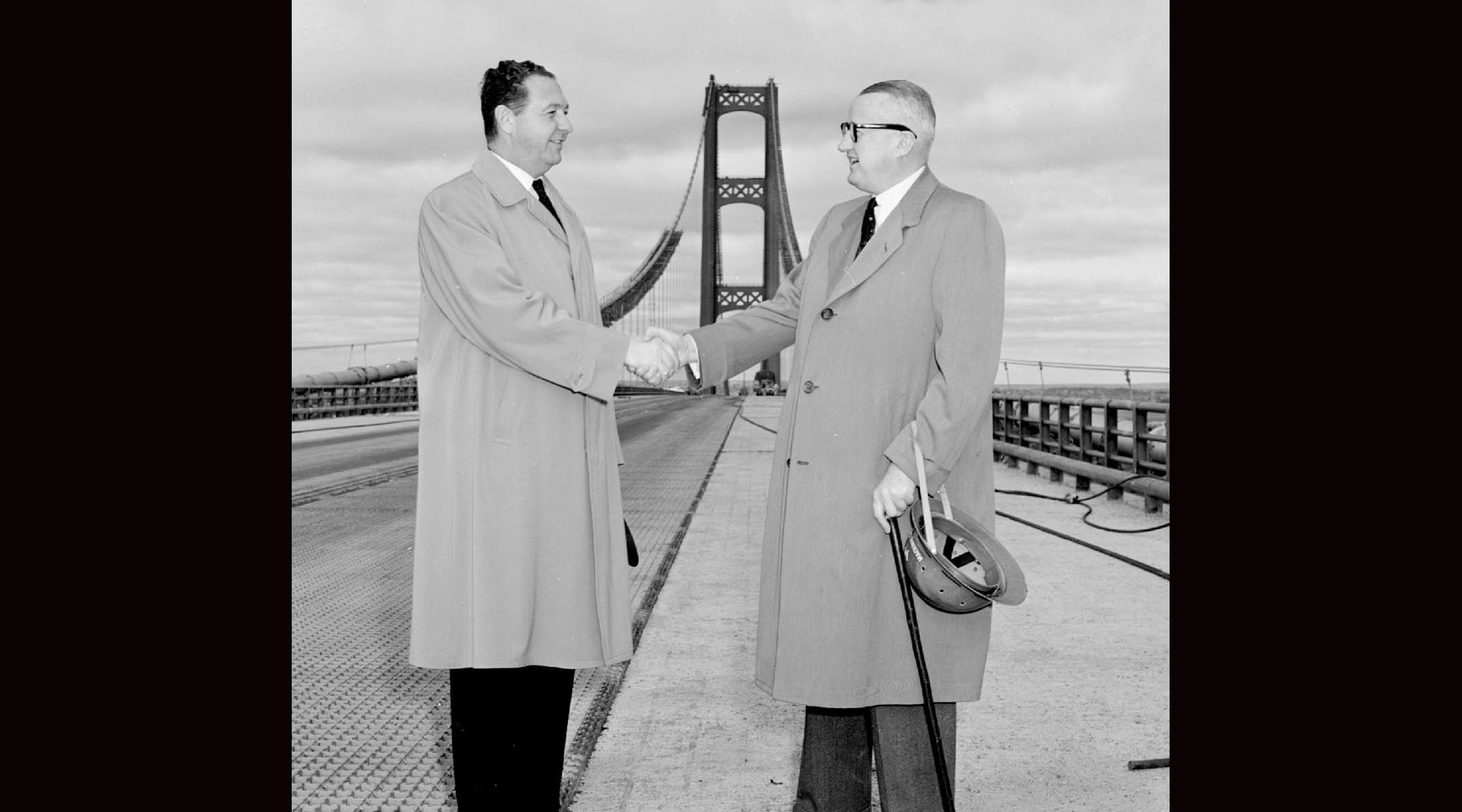

Lawrence Rubin (left) shakes hands with W. Stewart Woodfill, owner of the Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, on the Mackinac Bridge around the time of its completion in the 1950s. (Courtesy of the Mackinac Bridge Authority)

In 2020 the funeral home fell under new ownership, along with several others in the area. This year an ad appeared in the local newspaper listing the names of dozens of unclaimed remains at the homes, along with a notice that any still unaccounted for would soon be buried in a plot of the funeral home’s choosing.

That’s when a local friend of the bridge authority recognized one of those names — “L. Rubin” — and, shocked, made some calls. Soon leaders of B’Nai Israel, together with Rubin’s surviving colleagues from the bridge, raised funds and arranged for a proper Jewish burial. Raising the money was no issue. Everybody loved “Larry.”

“We mourned him 15 years ago. We’re celebrating him again today,” Bill Gnodtke, who served as chair of the Mackinac Bridge Authority after Rubin, said in an interview. “The fact that we can play a role in making this come to fruition, it makes me feel very good.”

***

Barbara Brown remembers the story well, because it happened to her grandfather.

It was a brutally cold winter day and Prentice Brown, a lawyer and Michigan senator, had to travel from his home in the Upper Peninsula to the state capital of Lansing, where he was due to argue a case before the state Supreme Court. The lakes were frozen over; the only option for transportation, the ferry, was useless. Prentice and his team set off on foot.

Only after crossing one ice hill, and seeing an expanse of not-yet-frozen-over water still separating them from land, did Prentice fully resolve: We need a bridge.

Michiganders had been trying for decades, almost since the Upper Peninsula had joined their state, to get a bridge built across the five-mile Strait of Mackinac. A lengthy suspension bridge known as “Galloping Gertie” had dramatically collapsed in Washington State in 1940, making Michigan legislators reluctant to try on their own. But Prentice Brown, after convincing Wall Street to help secure the bonds, recruited Rubin to ensure their bridge would be firmer and last the test of time.

Born outside Boston in 1912, Rubin enrolled at the University of Michigan and stuck around the state after college, working in public relations and for the state highway commission. In 1950, Brown hired him to oversee what would become the $100 million bridge project and Rubin moved to St. Ignace, into a house on the bay overlooking what would be the site of the bridge.

“Larry would say that the last things he saw at night were the lights of the bridge, and the first things he saw in the morning were the lights of the bridge,” Gnodtke recalled.

In June of 1957, the roads had still not yet been placed on the bridge. Yet by that November, miraculously, all construction had been completed and the bridge was open to the public. Rubin remained at the head of the bridge authority until his retirement in 1986, at which time the bridge had paid off its bonds through tolls. He remained a major bridge booster for the rest of his life, authoring books on its construction along with some short stories and novels (sometimes using a pseudonym, “Massie Davis”).

In St. Ignace, just north of the bridge, Rubin and the town’s other Jewish family would hold Passover seders at each other’s homes. For most Jewish holidays, though, they made the 45-minute drive south to B’Nai Israel, where Rubin served as secretary for years. He also served on the advisory board of the Anti-Defamation League and was involved with the Jewish Historical Society of Michigan, where he once penned an article for its journal titled, “Who’s Who in Northern Michigan Jewry.”

(L-r) Val Meyerson, immediate past president of Temple B’Nai Israel in Petoskey, Michigan, left, and the temple’s seasonal rabbi Debbie Masserano, May 28, 2025. B’Nai Israel was instrumental in arranging the belated funeral service for Lawrence Rubin, who died 15 years prior. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

The local Jewish population dates back to the 1700s, when the first Jew in the state of Michigan settled on Mackinac Island, a stone’s throw from where the bridge would be built centuries later. Jewish fur traders and other merchants have served the region’s miners and ironworkers ever since, though their ranks have thinned considerably: B’Nai Israel, which has roots in the 1890s and around 30 year-round member families today, is the largest of the area’s remaining synagogues.

Few of its active members today knew Rubin. The synagogue doesn’t employ a full-time rabbi; instead it flies in Masserano once a month from Seattle for services and other lifecycle events. (The number of member families swells to around 90 in the summer months, when Maya Leibovich, famous for being Israel’s first native-born ordained female rabbi, moves to Petoskey with her husband to minister.)

Today, a recently incorporated consortium, L’dor V’dor, helps provide services to six small congregations spread across the region — in Petoskey, Traverse City, Alpena, Hancock, Marquette, and Sault Ste. Marie (the Ontario side, also linked to the others by a Rubin bridge). Some of the area’s smaller congregations, including one in Iron Mountain on the western edge of the state, have shuttered in recent years.

Rubin believed deeply in preserving Jewish life in northern Michigan, and was a longtime secretary of B’Nai Israel. And when the news of his cremains’ discovery reached the temple, they knew Rubin’s only surviving family member would not be participating in any burial. So they took it upon themselves to do it.

“I told Bill, ‘Well, heck, let’s get him, so we can bury him,’” Val Meyerson, the temple’s immediate past president and director of the Petoskey Public Library, recalled. “This is a really heartwarming story, and a beautiful testament to small towns and people really working together to the betterment of the community.”

***

When it announced Rubin’s death in 2010, the bridge authority noted that condolences could be passed along to his second wife, Elma, and his son, David. Both were listed as living in St. Ignace at the time. David helped plan a public memorial for his father that year, held at a park in full view of the bridge.

But tracing what happened next is challenging. Elma, already in her nineties at the time, died in 2015. Nobody locally seems to have heard from David since, or knows how to get hold of him, though a LinkedIn profile with a close match for his biography indicates he has spent the last few years in New York working as a fact-checker in financial news.

Few who knew David in St. Ignace were willing to speak on the record about him. “I’m grateful to all of the people who made an appropriate internment possible,” Barbara Brown told JTA.

Requests for comment to phone numbers and email addresses associated with David Rubin were left unreturned or led to dead phone lines and inactive emails. Contact information for a “David Rubin” listed on the State Bar of California website with a St. Ignace address, and whose email address matched one Lawrence’s son had also used, also led to a dead end. (The bar association noted that his license to practice law in the state was suspended in 2012 due to failure to pay fees.)

Representatives for Temple B’Nai Israel said they had no way of reaching him. A spokesperson for the bridge authority said no one there knew how to reach him, either, while a spokesperson for the funeral home declined to share his contact info or pass along any message.

A representative for the Bentley Library, the University of Michigan research center housing Lawrence’s papers, declined to make David’s contact information available, but passed on a message to him through the postal service — to his St. Ignace address, the only one the library had on file. A request to interview David about his father, via the library, was not returned.

Photos of Lawrence Rubin with Michigan dignitaries from the Mackinac Bridge’s opening in 1957 were displayed at an oneg during a memorial service for Rubin held at Temple B’Nai Israel, Petoskey, Michigan, May 28, 2025. (Andrew Lapin/JTA)

Meanwhile, the funeral home holding Lawrence’s remains came under new ownership along with a handful of other local funeral homes. It soon became apparent that a large number of remains across all three homes had been unclaimed for years, and that at least a few families had been under the mistaken impression they’d already buried their loved ones.

A local TV news investigation did not uncover any evidence of unusual activity. In a statement, the home’s new owner said unclaimed remains were “not uncommon” in the funeral industry, listing a bevy of reasons why such a thing might happen, including miscommunication among next of kin and a mistaken belief that family has to pay to claim the remains.

Regardless, the home’s owner noted, “All families are notified to pick up the cremated remains multiple times.”

Some records of David Rubin’s relationship with his father are available. In 2011, a year after Lawrence died and while his cremains sat unclaimed, his alma mater at the University of Michigan listed an addition to its library’s collection of his papers.

The additions came, the university said, from his son David; they included letters David had written to Lawrence.

A visit to the archives in Ann Arbor provides a window into David and Lawrence’s relationship, which was often warm and loving, if colored with a tinge of knowing exasperation. David would address his father as “Chief” and himself as “Rube,” or “Your crazy kid who loves you.” In the 1990s, Lawrence helped put his son through law school in New York, and he proudly told his friends and family when David was appointed editor-in-chief of the law review.

The two also shared a love of creative writing, both having submitted short stories to magazines, and with David having appeared to complete a master’s degree in creative writing from Michigan prior to law school. One of David’s stories, titled “Dead Man’s Auction,” is told from the perspective of a dying store owner who regrets never having made up a will.

In a postcard from Spain, apparently sent after Olga’s death, David allowed some raw emotions to flow.

“Am thinking often of Mom but will feel okay again eventually. Hope the same for you. Thinking of you too and wish you were here,” he wrote to his dad. “Looking forward to seeing you soon and walking the bridge together again. Love & kisses, your punk.”

***

While the circumstances of Lawrence’s long wait to be buried certainly unsettled the gathered mourners in Petoskey, people also generally agreed that to dwell on them would be to miss the point. They preferred to remember the man and his accomplishments, and jumped at the chance to do so one more time.

At the funeral those who remembered Rubin shared stories of their time with him, tearing up as though he’d just passed the other day. Afterwards, attendees gathered at the temple for a small oneg with vintage photographs of Rubin’s role in the bridge’s construction on display next to some plates of pastries.

In Rubin’s final years, even when traveling became difficult, he still made it a point to stay involved with B’Nai Israel. Even into his nineties, he would make — increasingly with assistance — the 45-minute drive from his home in St. Ignace across the bridge, to attend services there.

“I’m happy to be here,” he would tell his fellow congregants. “I’m happy to be anywhere.”

JTA has documented Jewish history in real-time for over a century. Keep our journalism strong by joining us in supporting independent, award-winning reporting.